Why Did Egyptian Art And Architecture Often Depict Animals, Such As The Lion Body Of The Sphinx?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Sphinx-statue-631.jpg)

When Mark Lehner was a teenager in the late 1960s, his parents introduced him to the writings of the famed clairvoyant Edgar Cayce. During one of his trances, Cayce, who died in 1945, saw that refugees from the lost city of Atlantis buried their secrets in a hall of records under the Sphinx and that the hall would exist discovered before the finish of the 20th century.

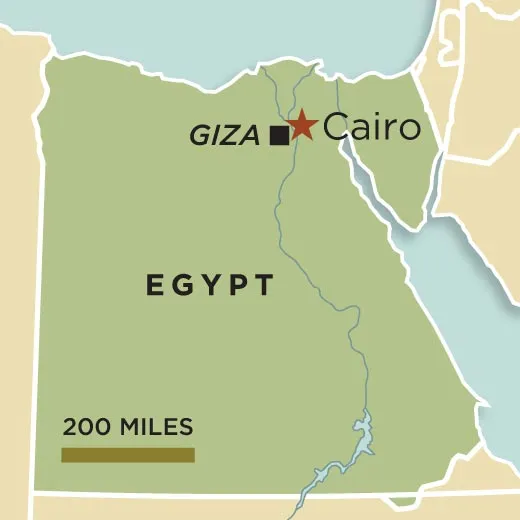

In 1971, Lehner, a bored sophomore at the Academy of North Dakota, wasn't planning to search for lost civilizations, simply he was "looking for something, a meaningful involvement." He dropped out of schoolhouse, began hitchhiking and ended up in Virginia Beach, where he sought out Cayce's son, Hugh Lynn, the head of a holistic medicine and paranormal enquiry foundation his father had started. When the foundation sponsored a grouping tour of the Giza plateau—the site of the Sphinx and the pyramids on the western outskirts of Cairo—Lehner tagged along. "Information technology was hot and dusty and non very royal," he remembers.

Still, he returned, finishing his undergraduate education at the American University of Cairo with support from Cayce'southward foundation. Even equally he grew skeptical almost a lost hall of records, the site's foreign history exerted its pull. "There were thousands of tombs of real people, statues of real people with real names, and none of them figured in the Cayce stories," he says.

Lehner married an Egyptian woman and spent the ensuing years plying his drafting skills to win work mapping archaeological sites all over Egypt. In 1977, he joined Stanford Research Establish scientists using state-of-the-art remote-sensing equipment to analyze the boulder under the Sphinx. They institute just the cracks and fissures expected of ordinary limestone formations. Working closely with a young Egyptian archaeologist named Zahi Hawass, Lehner also explored and mapped a passage in the Sphinx'southward rump, last that treasure hunters likely had dug it afterward the statue was built.

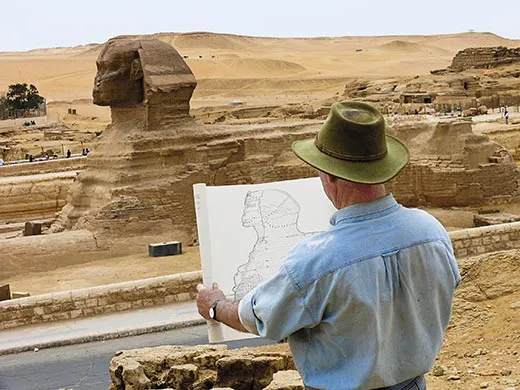

No human being endeavor has been more associated with mystery than the huge, aboriginal lion that has a man head and is seemingly resting on the rocky plateau a stroll from the cracking pyramids. Fortunately for Lehner, it wasn't simply a metaphor that the Sphinx is a riddle. Niggling was known for certain most who erected it or when, what it represented and precisely how information technology related to the pharaonic monuments nearby. So Lehner settled in, working for five years out of a makeshift part between the Sphinx's colossal paws, subsisting on Nescafé and cheese sandwiches while he examined every square inch of the structure. He remembers "climbing all over the Sphinx like the Lilliputians on Gulliver, and mapping it rock by rock." The result was a uniquely detailed film of the statue's worn, patched surface, which had been subjected to at least five major restoration efforts since ane,400 B.C. The research earned him a doctorate in Egyptology at Yale.

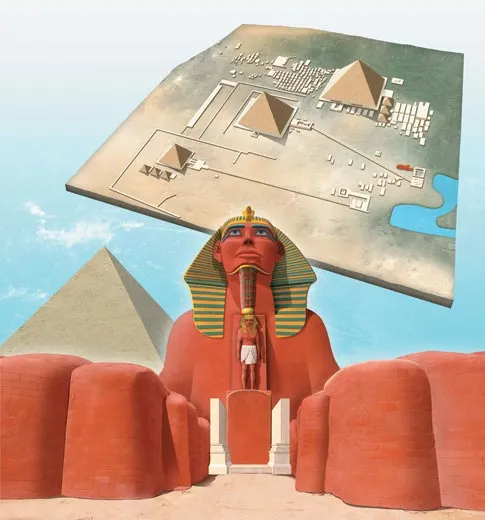

Recognized today as 1 of the world's leading Egyptologists and Sphinx authorities, Lehner has conducted field research at Giza during most of the 37 years since his first visit. (Hawass, his friend and frequent collaborator, is the secretarial assistant general of the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities and controls access to the Sphinx, the pyramids and other government-endemic sites and artifacts.) Applying his archaeological sleuthing to the surrounding two-square-mile Giza plateau with its pyramids, temples, quarries and thousands of tombs, Lehner helped confirm what others had speculated—that some parts of the Giza complex, the Sphinx included, make up a vast sacred car designed to harness the power of the lord's day to sustain the earthly and divine order. And while he long ago gave up on the fabled library of Atlantis, it'due south curious, in lite of his early wanderings, that he finally did detect a Lost City.

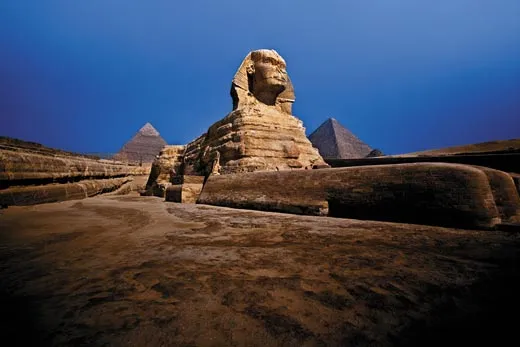

The Sphinx was not assembled piece past slice merely was carved from a single mass of limestone exposed when workers dug a horseshoe-shaped quarry in the Giza plateau. Approximately 66 feet tall and 240 feet long, it is one of the largest and oldest monolithic statues in the world. None of the photos or sketches I'd seen prepared me for the scale. Information technology was a humbling sensation to stand between the creature's paws, each twice my elevation and longer than a city bus. I gained sudden empathy for what a mouse must feel similar when cornered past a cat.

Nobody knows its original proper noun. Sphinx is the human-headed lion in aboriginal Greek mythology; the term likely came into use some 2,000 years after the statue was congenital. There are hundreds of tombs at Giza with hieroglyphic inscriptions dating back some 4,500 years, but non i mentions the statue. "The Egyptians didn't write history," says James Allen, an Egyptologist at Brown University, "so we have no solid testify for what its builders thought the Sphinx was....Certainly something divine, presumably the prototype of a king, just beyond that is anyone's guess." Likewise, the statue's symbolism is unclear, though inscriptions from the era refer to Ruti, a double lion god that sat at the entrance to the underworld and guarded the horizon where the dominicus rose and fix.

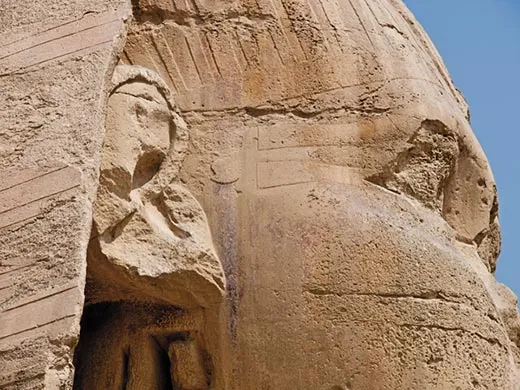

The face, though amend preserved than almost of the statue, has been battered past centuries of weathering and vandalism. In 1402, an Arab historian reported that a Sufi zealot had disfigured it "to remedy some religious errors." Yet there are clues to what the confront looked like in its prime. Archaeological excavations in the early 19th century institute pieces of its carved rock beard and a royal cobra emblem from its headdress. Residues of blood-red paint are still visible on the face, leading researchers to conclude that at some betoken, the Sphinx's entire visage was painted blood-red. Traces of bluish and yellow pigment elsewhere advise to Lehner that the Sphinx was once decked out in gaudy comic book colors.

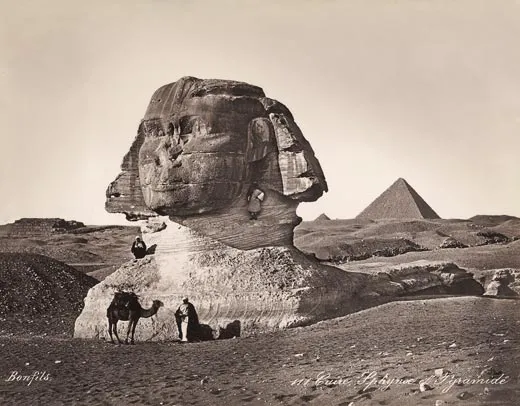

For thousands of years, sand buried the colossus up to its shoulders, creating a vast disembodied head atop the eastern edge of the Sahara. Then, in 1817, a Genoese adventurer, Capt. Giovanni Battista Caviglia, led 160 men in the starting time modern endeavor to dig out the Sphinx. They could not hold dorsum the sand, which poured into their excavation pits nigh as fast every bit they could dig it out. The Egyptian archaeologist Selim Hassan finally freed the statue from the sand in the late 1930s. "The Sphinx has thus emerged into the landscape out of shadows of what seemed to exist an impenetrable oblivion," the New York Times declared.

The question of who built the Sphinx has long vexed Egyptologists and archaeologists. Lehner, Hawass and others concord it was Pharaoh Khafre, who ruled Egypt during the Old Kingdom, which began around two,600 B.C. and lasted some 500 years earlier giving way to civil state of war and famine. It's known from hieroglyphic texts that Khafre's father, Khufu, built the 481-foot-tall Great Pyramid, a quarter mile from where the Sphinx would afterward be built. Khafre, following a tough act, constructed his ain pyramid, 10 feet shorter than his father's, also a quarter of a mile behind the Sphinx. Some of the evidence linking Khafre with the Sphinx comes from Lehner's research, but the idea dates dorsum to 1853.

That's when a French archeologist named Auguste Mariette unearthed a life-size statue of Khafre, carved with startling realism from blackness volcanic rock, amid the ruins of a edifice he discovered adjacent to the Sphinx that would afterward be chosen the Valley Temple. What'southward more, Mariette institute the remnants of a rock causeway—a paved, processional road—connecting the Valley Temple to a mortuary temple next to Khafre'due south pyramid. So, in 1925, French archeologist and engineer Emile Baraize probed the sand directly in front of the Sphinx and discovered yet another One-time Kingdom edifice—at present called the Sphinx Temple—strikingly similar in its ground program to the ruins Mariette had already constitute.

Despite these clues that a single master edifice programme tied the Sphinx to Khafre'due south pyramid and his temples, some experts continued to speculate that Khufu or other pharaohs had congenital the statue. So, in 1980, Lehner recruited a immature German geologist, Tom Aigner, who suggested a novel mode of showing that the Sphinx was an integral office of Khafre'southward larger edifice circuitous. Limestone is the result of mud, coral and the shells of plankton-like creatures compressed together over tens of millions of years. Looking at samples from the Sphinx Temple and the Sphinx itself, Aigner and Lehner inventoried the different fossils making upwards the limestone. The fossil fingerprints showed that the blocks used to build the wall of the temple must have come from the ditch surrounding the Sphinx. Apparently, workmen, probably using ropes and wooden sledges, hauled away the quarried blocks to construct the temple every bit the Sphinx was being carved out of the stone.

That Khafre arranged for structure of his pyramid, the temples and the Sphinx seems increasingly probable. "Most scholars believe, as I do," Hawass wrote in his 2006 book, Mountain of the Pharaohs, "that the Sphinx represents Khafre and forms an integral office of his pyramid complex."

Merely who carried out the backbreaking work of creating the Sphinx? In 1990, an American tourist was riding in the desert one-half a mile south of the Sphinx when she was thrown from her horse after it stumbled on a low mud-brick wall. Hawass investigated and discovered an Old Kingdom cemetery. Some 600 people were buried there, with tombs belonging to overseers—identified by inscriptions recording their names and titles—surrounded by the humbler tombs of ordinary laborers.

Near the cemetery, nine years later, Lehner discovered his Lost City. He and Hawass had been enlightened since the mid-1980s that there were buildings at that site. But it wasn't until they excavated and mapped the area that they realized it was a settlement bigger than ten football fields and dating to Khafre's reign. At its middle were 4 clusters of eight long mud-brick barracks. Each construction had the elements of an ordinary firm—a pillared porch, sleeping platforms and a kitchen—that was enlarged to suit around fifty people sleeping side by side. The billet, Lehner says, could have accommodated between 1,600 to two,000 workers—or more, if the sleeping quarters were on two levels. The workers' diet indicates they weren't slaves. Lehner'south team found remains of by and large male person cattle under 2 years old—in other words, prime number beefiness. Lehner thinks ordinary Egyptians may have rotated in and out of the work crew under some sort of national service or feudal obligation to their superiors.

This past fall, at the behest of "Nova" documentary makers, Lehner and Rick Dark-brown, a professor of sculpture at the Massachusetts College of Art, attempted to learn more about construction of the Sphinx by sculpting a scaled-downwards version of its missing nose from a limestone cake, using replicas of aboriginal tools institute on the Giza plateau and depicted in tomb paintings. Forty-five centuries ago, the Egyptians lacked iron or statuary tools. They mainly used stone hammers, along with copper chisels for detailed finished piece of work.

Bashing away in the yard of Chocolate-brown'south studio near Boston, Brownish, assisted by art students, found that the copper chisels became edgeless after only a few blows before they had to be resharpened in a forge that Dark-brown constructed out of a charcoal furnace. Lehner and Brown gauge one laborer might cleave a cubic human foot of stone in a calendar week. At that charge per unit, they say, it would accept 100 people iii years to complete the Sphinx.

Exactly what Khafre wanted the Sphinx to practise for him or his kingdom is a matter of debate, but Lehner has theories virtually that, too, based partly on his work at the Sphinx Temple. Remnants of the temple walls are visible today in front end of the Sphinx. They surround a courtyard enclosed by 24 pillars. The temple program is laid out on an east-westward centrality, clearly marked by a pair of small niches or sanctuaries, each about the size of a closet. The Swiss archeologist Herbert Ricke, who studied the temple in the late 1960s, concluded the axis symbolized the movements of the sun; an east-west line points to where the dominicus rises and sets twice a year at the equinoxes, halfway between midsummer and midwinter. Ricke further argued that each pillar represented an hour in the lord's day'due south daily circuit.

Lehner spotted something possibly fifty-fifty more remarkable. If you stand in the eastern niche during sunset at the March or September equinoxes, you see a dramatic astronomical event: the sun appears to sink into the shoulder of the Sphinx and, beyond that, into the due south side of the Pyramid of Khafre on the horizon. "At the very same moment," Lehner says, "the shadow of the Sphinx and the shadow of the pyramid, both symbols of the male monarch, become merged silhouettes. The Sphinx itself, information technology seems, symbolized the pharaoh presenting offerings to the sun god in the court of the temple." Hawass concurs, saying the Sphinx represents Khafre as Horus, the Egyptians' revered regal falcon god, "who is giving offerings with his two paws to his begetter, Khufu, incarnated every bit the sun god, Ra, who rises and sets in that temple."

As intriguing, Lehner discovered that when one stands near the Sphinx during the summertime solstice, the sunday appears to set midway between the silhouettes of the pyramids of Khafre and Khufu. The scene resembles the hieroglyph akhet, which tin can be translated as "horizon" but also symbolized the cycle of life and rebirth. "Even if coincidental, it is hard to imagine the Egyptians not seeing this ideogram," Lehner wrote in the Archive of Oriental Research. "If somehow intentional, it ranks equally an example of architectural illusionism on a grand, perhaps the grandest, scale."

If Lehner and Hawass are right, Khafre'due south architects bundled for solar events to link the pyramid, Sphinx and temple. Collectively, Lehner describes the circuitous as a cosmic engine, intended to harness the ability of the sunday and other gods to resurrect the soul of the pharaoh. This transformation not only guaranteed eternal life for the dead ruler only besides sustained the universal natural gild, including the passing of the seasons, the annual flooding of the Nile and the daily lives of the people. In this sacred bicycle of death and revival, the Sphinx may have stood for many things: as an image of Khafre the dead king, as the sun god incarnated in the living ruler and as guardian of the underworld and the Giza tombs.

But it seems Khafre'due south vision was never fully realized. There are signs the Sphinx was unfinished. In 1978, in a corner of the statue'due south quarry, Hawass and Lehner found 3 stone blocks, abandoned equally laborers were dragging them to build the Sphinx Temple. The due north edge of the ditch surrounding the Sphinx contains segments of bedrock that are only partially quarried. Hither the archaeologists besides institute the remnants of a workman's lunch and tool kit—fragments of a beer or h2o jar and rock hammers. Apparently, the workers walked off the job.

The enormous temple-and-Sphinx complex might accept been the pharaoh's resurrection machine, but, Lehner is fond of saying, "nobody turned the key and switched information technology on." By the time the Onetime Kingdom finally broke apart around ii,130 B.C., the desert sands had begun to repossess the Sphinx. It would sit down ignored for the next seven centuries, when information technology spoke to a young royal.

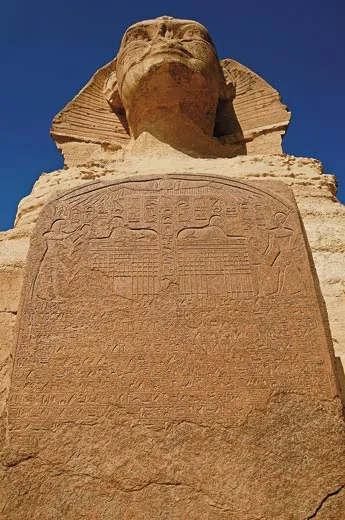

According to the legend engraved on a pinkish granite slab between the Sphinx'south paws, the Egyptian prince Thutmose went hunting in the desert, grew tired and lay downwardly in the shade of the Sphinx. In a dream, the statue, calling itself Horemakhet—or Horus-in-the-Horizon, the primeval known Egyptian name for the statue—addressed him. It complained near its ruined body and the encroaching sand. Horemakhet then offered Thutmose the throne in exchange for help.

Whether or not the prince actually had this dream is unknown. But when he became Pharaoh Thutmose IV, he helped introduce a Sphinx-worshiping cult to the New Kingdom (1550-1070 B.C.). Across Egypt, sphinxes appeared everywhere in sculptures, reliefs and paintings, often depicted as a potent symbol of royalty and the sacred power of the lord's day.

Based on Lehner's assay of the many layers of stone slabs placed similar tilework over the Sphinx's crumbling surface, he believes the oldest slabs may engagement back every bit far every bit 3,400 years to Thutmose'due south time. In keeping with the legend of Horemakhet, Thutmose may well have led the get-go attempt to restore the Sphinx.

When Lehner is in the United States, typically about six months per year, he works out of an part in Boston, the headquarters of Ancient Egypt Research Assembly, a nonprofit organization Lehner directs that excavates the Lost City and trains young Egyptologists. At a meeting with him at his part this past fall, he unrolled 1 of his endless maps of the Sphinx on a table. Pointing to a section where an old tunnel had cutting into the statue, he said the elements had taken a toll on the Sphinx in the start few centuries subsequently information technology was congenital. The porous rock soaks upwards moisture, degrading the limestone. For Lehner, this posed withal another riddle—what was the source of and then much wet in Giza's seemingly bone-dry desert?

The Sahara has not always been a wilderness of sand dunes. High german climatologists Rudolph Kuper and Stefan Kröpelin, analyzing the radiocarbon dates of archaeological sites, recently ended that the region'southward prevailing climate pattern changed around viii,500 B.C., with the monsoon rains that covered the torrid zone moving northward. The desert sands sprouted rolling grasslands punctuated by verdant valleys, prompting people to begin settling the region in 7,000 B.C. Kuper and Kröpelin say this green Sahara came to an terminate between 3,500 B.C. and 1,500 B.C., when the monsoon belt returned to the tropics and the desert reemerged. That engagement range is 500 years afterwards than prevailing theories had suggested.

Further studies led by Kröpelin revealed that the render to a desert climate was a gradual process spanning centuries. This transitional period was characterized past cycles of ever-decreasing rains and extended dry spells. Support for this theory can exist found in recent research conducted by Judith Bunbury, a geologist at the Academy of Cambridge. After studying sediment samples in the Nile Valley, she concluded that climate change in the Giza region began early on in the Onetime Kingdom, with desert sands arriving in strength late in the era.

The work helps explain some of Lehner'southward findings. His investigations at the Lost Metropolis revealed that the site had eroded dramatically—with some structures reduced to ankle level over a catamenia of three to iv centuries subsequently their structure. "Then I had this realization," he says, "Oh my God, this fizz saw that cut our site downwardly is probably what also eroded the Sphinx." In his view of the patterns of erosion on the Sphinx, intermittent wet periods dissolved salt deposits in the limestone, which recrystallized on the surface, causing softer stone to crumble while harder layers formed large flakes that would be blown abroad by desert winds. The Sphinx, Lehner says, was subjected to constant "scouring" during this transitional era of climate change.

"Information technology'south a theory in progress," says Lehner. "If I'one thousand right, this episode could correspond a kind of 'tipping point' between different climate states—from the wetter conditions of Khufu and Khafre's era to a much drier surround in the final centuries of the Erstwhile Kingdom."

The implication is that the Sphinx and the pyramids, epic feats of applied science and architecture, were built at the finish of a special time of more dependable rainfall, when pharaohs could marshal labor forces on an epic calibration. Just then, over the centuries, the landscape dried out and harvests grew more precarious. The pharaoh's primal authorization gradually weakened, allowing provincial officials to assert themselves—culminating in an era of civil war.

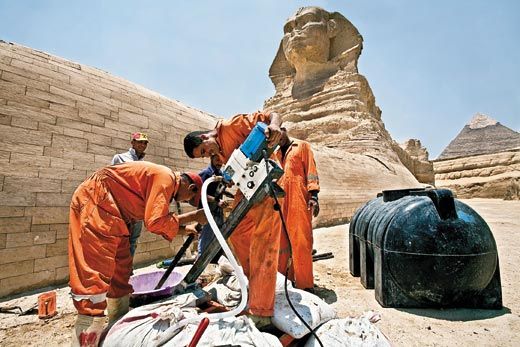

Today, the Sphinx is nonetheless eroding. Three years ago, Egyptian authorities learned that sewage dumped in a nearby culvert was causing a rise in the local water table. Moisture was drawn up into the body of the Sphinx and large flakes of limestone were peeling off the statue.

Hawass bundled for workers to drill test holes in the boulder effectually the Sphinx. They found the h2o tabular array was merely 15 anxiety beneath the statue. Pumps have been installed nearby to divert the groundwater. Then far, so good. "Never say to anyone that we saved the Sphinx," he says. "The Sphinx is the oldest patient in the world. All of u.s.a. accept to dedicate our lives to nursing the Sphinx all the time."

Evan Hadingham is senior science editor of the PBS series "Nova." Its "Riddles of the Sphinx" aired on Jan 19.

Source: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/uncovering-secrets-of-the-sphinx-5053442/

Posted by: mercerciat1967.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Why Did Egyptian Art And Architecture Often Depict Animals, Such As The Lion Body Of The Sphinx?"

Post a Comment